As a 4th generation Chinese with ties to Hawaii (thus my daughter’s name), I’m somewhat removed from my heritage culture. I grew up on Shake’N Bake chicken and broccoli, didn’t learn how to use chopsticks until a 3rd grade field trip to San Francisco’s Chinatown and never really considered myself Asian as a child since I grew up in a predominantly Caucasian neighborhood.

Even so, I like to say that my stomach is Asian; there’s pretty much nothing that I don’t enjoy eating. Besides a lifelong love of dim sum, I adore chicken feet, pigs ear, fish eyes and much more. My childhood exposure to Chinese food was mainly Cantonese, but I’ve since expanded my palate to include dishes from various other regions. However, the vast world of Chinese cuisine is still widely unknown to me.

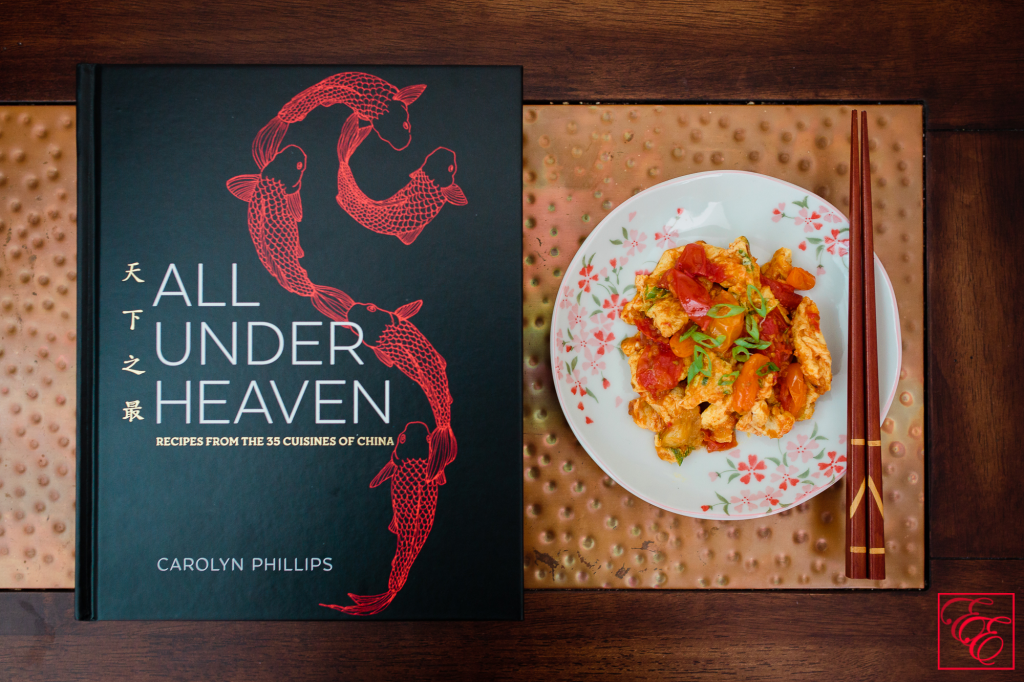

I would love to learn more about regional Chinese cuisine, and as soon as I read one page of “All Under Heaven: Recipes from the 35 Cuisines of China” by Carolyn Phillips, it was evident that she would be a great armchair instructor.

A California-based cookbook author and blogger at Madame Huang’s Kitchen, Carolyn Phillips used her fluency in Chinese as a translator in Taiwan in the 1980s. During her spare time, she ate, discussed, and learned how to cook a wide range of China’s cuisines and teas. Once back in the US, she continued researching Chinese traditional recipes and classic cooking styles. She now devotes herself to food writing, and this is her first cookbook.

“All Under Heaven: Recipes from the 35 Cuisines of China” is a masterful compilation of some of her favorite recipes from five major regions of China: the North and Manchurian Northeast (e.g. Beijing), the Yangtze River region (e.g. Shanghai), the Coastal Southeast (e.g. Hong Kong and Guangdong, which is where my ancestors are from), the Central Highlands (e.g. Hunan), and the Northwest (e.g. Tibet). I respect the care she took in researching to note how regional flavors and ingredients are defined and overlap, how recipes travel and evolve across regions, and how people of the region (e.g. invaders or immigrants) have informed local flavors. She aptly sums up her taxonomy and categorization with the guideline “you eat what you speak”. In other words, delineations of regional cuisines can be aligned with related dialect(s), of which China has 250+.

As a cookbook enthusiast who loves losing herself in a rich narrative of a recipe’s ‘soul’ and digging into the nuances of how to make an authentic, successful dish (based upon ingredient accuracy and detailed cooking technique explanations), this book hit everything I could hope for. It contains tidbits of China’s culinary history, stories about recipe origins/evolution, illustrated cooking techniques, and clearly-explained recipes. Sprinkled throughout the book are delicate pen illustrations, encyclopedia-like footnotes of cooking advice, and recipe names written in traditional characters and pinyin above the English description (a lovely addition for those who want to be able to pronounce, analyze or reference the traditional recipe name).

As example of Carolyn’s straight-forward expertise that makes the book so valuable, here is a simple recipe whose success lies entirely in her details.

It’s a dish of scrambled eggs cooked with tomato. Up until now, my knowledge was to 1) chop tomatoes into bite-size pieces, 2) crack and mix eggs in a bowl, and 3) stir-fry both ingredients in an oiled wok/pan until the mixture is moistly-cooked, flavoring to taste with salt. Needless to say, my execution of the dish has been wholly unremarkable. Here is hers, for (delicious) comparison.

Tomatoes and Eggs (Xi1hong2shi4 chao3 ji1zi3)

“… There are a few secrets to making this popular vegetarian recipe work. First, the tomatoes have to be deliciously ripe, and the eggs should be fresh. Second, the tomatoes should be in large enough pieces that they do not mush up. Third – and this is where most restaurant versions fail – the tomatoes should be fried in oil with aromatics and a touch of sugar until they almost caramelize. Their juices should concentrate into a thick marmalade; it’s this juice that coats each yellow egg curd and makes the dish stand out. Finally, season this dish with salt rather than soy sauce to keep the flavors sharp and the colors bright.”

Ingredients

- 1 lb very tasty red tomatoes of any kind (e.g. cherry and plum tomatoes, which keep their shape well)

- 5 T peanut of vegetable oil, divided into 3 T and 2 T

- 1/2 t sea salt

- 1 T peeled and finely chopped fresh ginger

- 2 green onions, trimmed and finely chopped, whites and greens in separate piles

- 1/2 to 1 t sugar

- freshly ground black pepper

- 4 large eggs, lightly beaten

Instructions

- Cut the tomatoes into pieces about 1″ wide and 1/2″ thick. If you are using cherry or plum tomatoes, cut them in half. Taste a tomato – if it is very sweet, use 1/2 t sugar in Step 2; otherwise, use 1 t.

- Place a wok over high heat, and when it is hot, swirl in 3 T of the oil and the salt. Fry the ginger and the whites of the onions until they are golden, and then add the sliced tomatoes. Lower the heat to medium-high and fry them, shaking and turning them over every 30 seconds or so. When the juice reduces to a few tablespoons, sprinkle on the sugar and pepper, and toss the tomatoes. Continue to cook them until you can smell the sugar and bits of caramel have formed on your spatula. Scrape the tomatoes out onto a plate.

- Return the wok to medium-high heat and swirl in the remaining 2 T oil. Stir the onion greens into the eggs and pour the eggs into the wok. Flip the eggs over as they solidify and brown until they have formed a soft, golden omelet. Chop up the omelet with your spatula and then toss in the cooked tomatoes. Serve hot.

Variation: Some people like to make a creamier dish, where the eggs turn custard rather than form large curds. To do this, keep the tomatoes in the wok at the end of Step 2 and stir the beaten eggs and onion greens into the tomatoes. Lightly toss everything together until the eggs have cooked through.

Let me tell you, the dish tasted as incredible as it looks and sounds. The tomatoes, green onion, and ginger reduced into a rich sweet-savory umami-filled sauce with a fresh flavor. Coating pieces of tender, moist egg curds and served with hot rice, it became a restaurant-worthy dish that had my taste testers smacking their lips and finishing every last bit. It’s incredible how such a truly delicious dish comes from a few simple ingredients. I highly recommend trying this dish, and am confident that you would be equally pleased with all of her other recipes.

True cooking success lies entirely in the details, and I’m thrilled to have Carolyn’s detail-oriented, expert voice lead me on this written culinary journey through China. I very much look forward to poring over each and every page to learn about the beautiful, fascinating nuances of my ancestor’s culture!

xoxo and aloha,

![]()

[Disclosure: I received a copy of this book from Blogging For Books for reviewing purposes. All content herein solely reflects my personal thoughts and opinions.]